Check out the original blog post here at the UN Foundation.

There’s the pandemic you know about, and all too well. It’s rightfully crowding the headlines of your newspaper and occupying the minds of government leaders. It’s taking loved ones, imperiling heroes in scrubs, threatening neighbors at the cash register, and suddenly turning parents everywhere into teachers.

Then, there’s the shadow pandemic, which is rapidly unraveling the limited, but precious, progress that the world has made toward gender equality in the past few decades. As summarized by a new UN report about COVID-19 and girls and women, this shadow pandemic can be seen in a spike in domestic violence as girls and women are sheltering-in-place with their abusers; the loss of employment for women who hold the majority of insecure, informal and lower-paying jobs; the risk shouldered by the world’s nurses, who are predominately women; and the rapid increase in unpaid care work that girls and women mostly provide already. The current emergency is poised to deeply exacerbate a stubborn one: while early reports suggest that men are more likely to succumb to COVID-19, the social and economic toll will be paid, disproportionately, by the world’s girls and women.

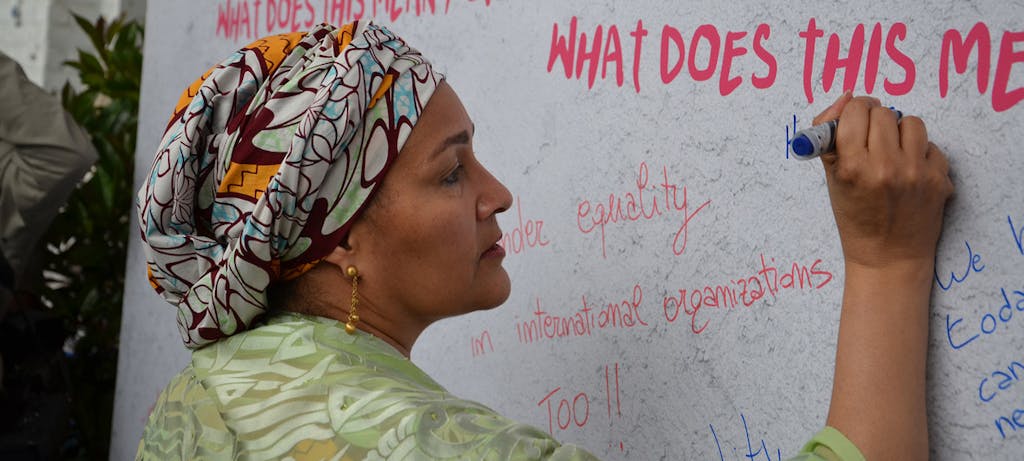

The UN’s bracingly clear policy guide makes clear the stakes and what governments and their people must do now to ensure their response to the COVID-19 crisis does not intensify the crisis of gender inequality. It includes ensuring women’s equal representation in all COVID-19 response planning and decision-making; driving transformative change for equality by addressing the care economy, paid and unpaid; and targeting women and girls in all efforts to address the socio-economic impact of COVID-19.

These recommendations together illuminate a critical element of the global response and recovery: girls and women are not just uniquely vulnerable to many of the dynamics of this crises but are also the leaders and problem-solvers that communities depend on, acting as frontline responders, healthcare workers, and community organizers and volunteers. Thus, the world can’t sideline gender equality now. Equality has to be at the heart of the response.

From the economy, to their health systems, to their homes, here is how COVID-19 is affecting girls and women.

Women and COVID-19 in the Economy

“Across the globe, women earn less, save less, hold less secure jobs, are more likely to be employed in the informal sector. They have less access to social protections and are the majority of single-parent households. Their capacity to absorb economic shocks is therefore less than that of men.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

The COVID-19 pandemic is clearly aggravating economic inequalities faced by women. A new study suggests “the COVID-19 pandemic will have a disproportionate negative effect on women and their employment opportunities. The effects of this shock are likely to outlast the actual epidemic.”

Specifically, an estimated 740 million women around the world work in the informal economy.

In developing economies informal work makes up 70 percent of women’s employment, and informal jobs are the first to disappear in times of economic uncertainty. In fact, new research shows that the sectors that have been most affected by the COVID-19 crisis so far are those with high levels of women workers, including the restaurant and hospitality business, as well as the travel sector.

Lessons from Liberia during the Ebola crisis should be considered. In Liberia up to 85 percent of daily market traders are women. They suffered higher levels of unemployment and loss of livelihood than men during the crisis and, while men’s economic activity returned to pre-crisis levels, the effect on women’s economic security and livelihoods lasted much longer.

In response, the UN recommends that as governments enact fiscal relief measures, they must build economic and social policies that place women’s economic lives at the heart of the pandemic response and recovery plans, including putting cash in women’s hands and extending basic protections to informal workers.

Women and COVID-19 in Health Systems

“Women and girls have unique health needs, but they are less likely to have access to quality health services, essential medicines and vaccines, maternal and reproductive health care, or insurance coverage for routine and catastrophic health costs, especially in rural and marginalized communities.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

In Latin America and the Caribbean an estimated 18 million additional women will lose regular access to modern contraceptives because of the pandemic. Similar reports are coming from other regions around the world as clinics shut and supply chains grind to a halt. The scarcity and diversion of attention and critical resources from basic health provisions may increase maternal mortality and morbidity, adolescent pregnancy, HIV transmission and sexually transmitted diseases.

The Ebola crisis is again illustrative. The number of women who died in childbirth in West Africa increased by 70 percent during the Ebola crisis as resources were diverted to Ebola response efforts.

In addition, because girls and women are less likely to have an education and are more likely to be illiterate, they may not benefit from public health messaging that is accessible, culturally appropriate and understandable. The UN report adds that restrictive social norms and gender stereotypes can also limit women’s ability to seek or benefit from health services, even when there isn’t a widespread health crisis and certainly in the midst of one.

“Special attention needs to be given to the health, psychosocial needs and work environment of frontline female health workers, including midwives, nurses, community health workers, as well as facility support staff.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

At the same time, it’s women who are answering the call for a surging demand for healthcare. Globally, women make up 70 percent of healthcare workers, and in hot spots such as China’s Hubei Province and the United States, they make up 90 percent and 78 percent respectively. Women also do most of the support jobs at health facilities, including the cleaning, laundry, and food service. Thus, they are more likely to be exposed to the virus.

The shortage of essential personal protective equipment (PPE) has been a more troubling aspect of the pandemic. It’s often noted that women have less access to PPE, or equipment that is correctly sized. Masks and other equipment designed and produced using the ‘default man’ size often leave women more at risk.

The UN advises that health systems consider and respond to the heightened vulnerability of female frontline workers and community volunteers and make provisions for standard health services to be continued, especially for sexual and reproductive health care.

Women and COVID-19 at Home

“The COVID-19 global crisis has made starkly visible the fact that the world’s formal economies and the maintenance of our daily lives are built on the invisible and unpaid labor of women and girls.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

Globally, girls and women on average do three times more unpaid care work than men, a number that is likely to skyrocket as all household chores have to be managed at home and while more than 1.52 billion (87 percent) children are at home instead of school. Girls and women are likely taking on full-time childcare and homeschooling, tasks that generally get assigned to a household’s girls and women, while also serving as the caregivers for the sick and elderly in the house.

As Mohammad Naciri, head of UN Women in Asia describes, “An even greater burden is placed on women where health systems are overloaded or schools are closed, as care for children or sick family members largely falls on women.”

Furthermore, the majority of single parents are women (21 percent of children in the U.S. live with their mother only, compared to four percent with their father), placing an even greater burden on mothers who have no other help. Ultimately, this unpaid labor burden leaves women less time for paid work, education, and career advancement, which fuels existing economic and social inequalities. The pandemic is making this existing problem more visible, and a bigger challenge for girls and women.

“Crowded homes, substance abuse, limited access to services and reduced peer support are exacerbating these conditions. Before the pandemic, it was estimated that one in three women will experience violence during their lifetimes. Many of these women are now trapped in their homes with their abusers.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

COVID-19 quarantining has caused a spike in domestic violence levels. As the Secretary-General recently stated, “We know lockdowns and quarantines are essential to suppressing COVID-19. But they can trap women with abusive partners.” There have already been staggering increases in domestic violence levels since quarantine measures have been enacted. Reports of domestic violence in France have increased by 30 percent since the lockdown began on March 17th, and similar increases have been reported across Europe and North America. Most glaringly, police reports in China showed that domestic violence levels tripled during the outbreak.

The UN cautions that while it is too early to have comprehensive data, reporting is surging, upwards of 25 percent in countries with reporting systems in place. In some countries reported cases have doubled. And, the UN cautions, violence against women is taking on a new complexity: exposure to COVID-19 is being used as a threat. “Abusers are exploiting the inability of women to call for help or escape and women risk being thrown out on the street with nowhere to go.”

Meanwhile, support services are highly strained as organizations focused on gender-based violence are already facing reduced operations and shut-downs.

The UN has provided guidance for governments, including a call to integrate prevention efforts and services to respond to violence against women into COVID-19 response plans; to designate domestic violence shelters as essential services and increasing resources to them, and to civil society groups on the front line of response; and to expand the capacity of shelters for victims of violence by re-purposing other spaces, such as empty hotels, or education institutions.

The UN will also use the Spotlight Initiative, its partnership with the European Union, which represents the world’s largest single investment in ending violence against women and girls, to work with governments to scale up their activities in response to the new challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Women and COVID-19 in Society, in Data, and in Fragile Contexts

“Evidence across sectors, including economic planning and emergency response, demonstrates unquestioningly that policies that do not consult women or include them in decision-making are simply less effective, and can even do harm. Beyond individual women, women’s organizations who are often on the front line of response in communities should also be represented and supported.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

Globally, 73 percent of executives in global health are men, while women, as noted, make up 70 percent of health workers. Global Health 50/50 studies from over the past three years find that “the number of women reaching the top has barely budged in the global health space.”

Occupational segregation by gender in the health sector is both deep and universal, with women health workers concentrated into lower status, lower paid or unpaid roles. Men make the decisions. Women do the work. But, without women’s expertise and input, no COVID-19 plans or policies will be sufficient to address the crisis. Operation COVID 50/50, a campaign for inclusive pandemic leadership, has issued five calls to action to strengthen the global response to COVID-19 and prepare health systems for future pandemics, calling for women’s inclusion, leadership, and representation.

The invisibility of women extends to global data sets. As our Data2X colleagues advise, experiences and lessons from past Zika and Ebola outbreaks demonstrate that gender analysis, informed by sex- and age-disaggregated data, is vital to meet particular needs of women, girls, boys, and men. The absence of sex-disaggregated data can impede evidence-based policy responses. Routine and regular collection, public reporting and the use of disaggregated data is vital to our understanding of who is most affected by COVID-19 and why.

While there is currently no global standard or mechanism for national or sub-national reporting of data, UN Women has launched an effort to collect and share sex-disaggregated country data, as well as ten policy priorities for a data driven response.

“The COVID-19 pandemic poses devastating risks for women and girls in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.” – Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

Humanitarian emergencies, from natural disasters to armed conflict to health epidemics, have consistently resulted in a disproportionate loss of health, dignity and rights for girls and women. COVID-19 side effects for girls and women, including increased violence, unpaid care burdens and health risks, will be especially acute for women living in conflict zones or refugee camps, places where there is often a lack of clean water, sanitation systems, and the ability to practice physical distancing. Delivery of relief supplies is being affected by lockdowns, too.

However, as is true in any other context, women living in places affected by humanitarian emergencies and conflict will be essential leaders in the response and recovery. Therefore, including them in consultation and decision-making, and ensuring they fully benefit from the right policies and tactical responses, is all the more critical.

Two Pandemics, One Response

“The pandemic is deepening pre-existing inequalities, exposing vulnerabilities in social, political and economic systems which are in turn amplifying the impacts of the pandemic.” – UN Secretary-General António Guterres, Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women

A pandemic amplifies and heightens all existing inequalities. Gender inequality plagued societies long before COVID-19, but it doesn’t have to define the response to it. Some will argue that we can’t focus on gender equality now. Others will say that it can wait until after crisis. But that’s a false choice, as it is a mistake to see them as wholly separate. Instead, the pandemic you know well is accelerating the one that you also live with, even if you can’t always see it.

The answer to improving the health of our societies and the health of our global population is the same: “Put women and girls at the center of efforts to recover from COVID-19.”